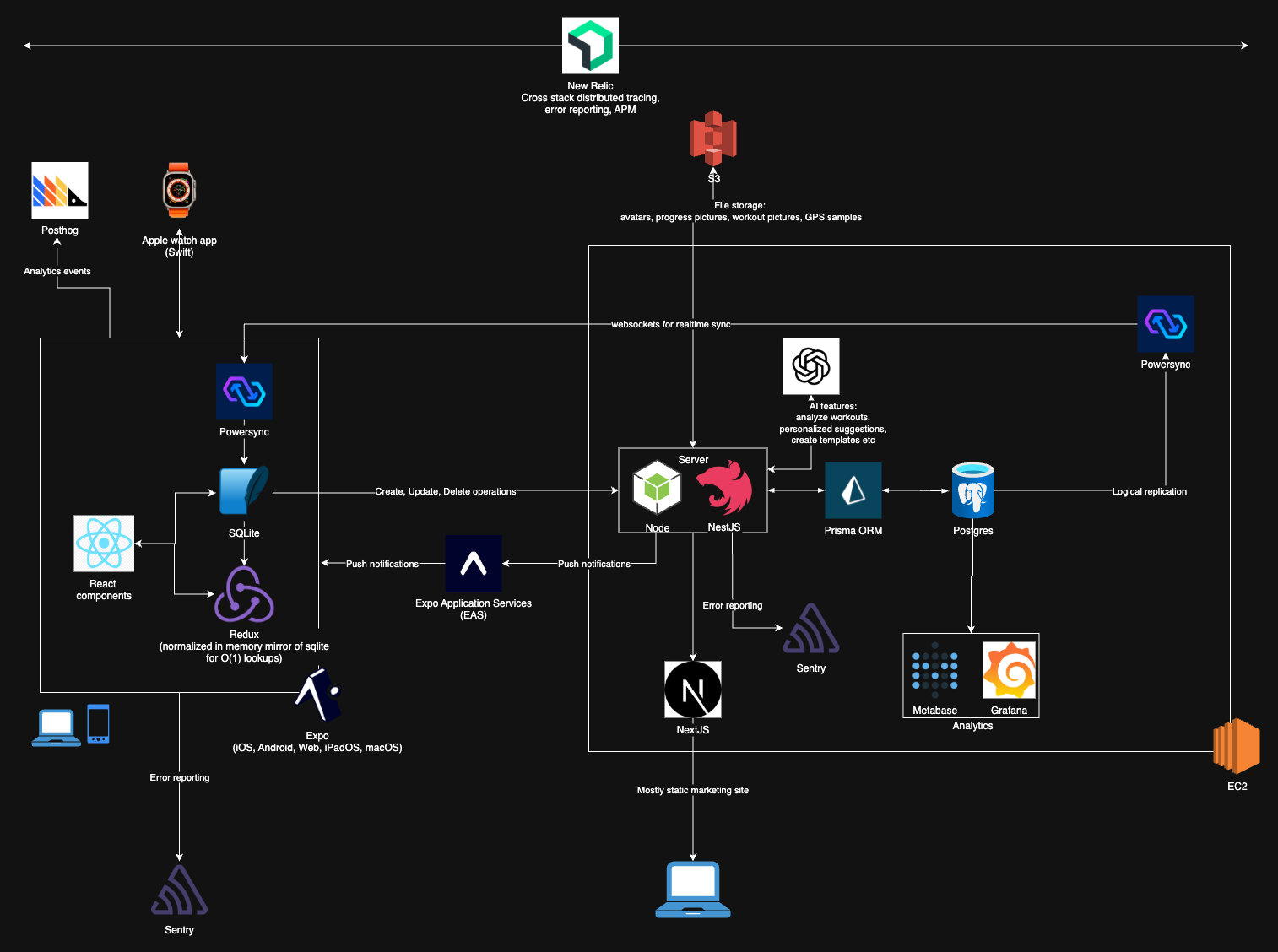

I’ve previously written a little bit about the tech stack behind my personal workout tracking app here. A few fundamental things have changed since then, which I think warrants this post.

The Problem

My old architecture was able to meet most system goals I’d started with. However, I found that there were a few scalability problems with my approach, which requires some background to understand.

Context

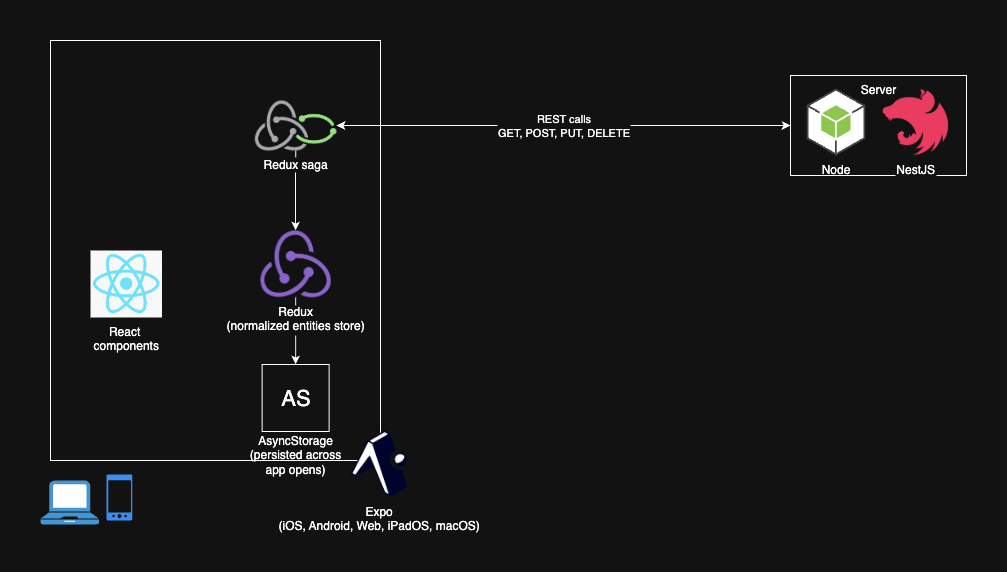

Below is a simplified diagram showing how data is exchanged between the client app and the server, through HTTP calls.

Here’s what a data fetching flow looked like:

Here’s what a data fetching flow looked like:

- A redux action is dispatched requesting the data to be fetched

- The action is intercepted by an async redux middleware (saga)

- The saga makes an async

fetchrequest to the backend and receives a payload - The payload is normalized into a structure that allows for really fast (usually

O(1)) lookups of data, and stored in redux. Normalization also means that the same entity always have a single source of truth.- For example let’s say the

Userobject is returned both by a/logincall and a/users/:idcall. Having a normalized store will mean that the last received data is what all views see.

- For example let’s say the

- Most of the redux store (including the normalized entities) are also persisted to

AsyncStorage(using redux-persist) for offline support

A flow involving an update to the database would look something like this:

- A redux action is dispatched requesting some data be written to the server

- The redux store is optimistically updated with the new data by a saga

- A saga makes the actual async

fetchrequest and does a few things based on the status code and what entity the operation is being performed on:- If it succeeded, the data received is normalized and saved into redux (often this will be the same as the optimistic update already made)

- If the call failed

- If the failure was because the server was down or the device is offline, and if the operation is being performed on specific entities, the optimistic update stays, and the server operation is queued up and stored into async storage to retry at a later time

- If the failure was because the server rejected the update, or if the operation is performed on entities not core to the flow of “tracking a workout”, the optimist update is rolled back

Problem 1: maintainability

As you can probably imagine, a retry flow like this, written by hand, gets very dicey very quickly. It leads to tons of edge cases, like:

- What happens if a retry fails? Should there be a limit to how many times something can be retried, or should the queue be allowed to grow indefinitely?

- What happens if we have two calls - A and B, and A fails, but B doesn’t, but B invalidates A. For example:

A. Update the number of reps on a set to 10 (failed)

B. Delete the set (succeeded)

- Now you’ve gotten to a state where retrying A will always result in a failure, the operation needs to be removed from the queue

- How do you handle schema drift? You could always have a client come back online that hasn’t communicated with the server in a long time. It would be a terrible experience if they lost data because the server no longer recognizes queued up operations.

Problem 2: developer experience

From a workload point of view, adding features is pretty costly. It often involves writing a decent amount of code each time I want to build a new feature:

- Migrations to update table structure

- Server code to handle CRUD operations

- Client code to handle communicating with the server through HTTP calls. This involves quite bit:

- New redux actions

- Code to normalize new entities

- Keeping types in sync with server responses

- And as described before, handling offline support

The solution

Surely there had to be a better way - the problems I’ve outlined above aren’t unique to my app.

This is where I came across the concept of sync engines. Sync engines aren’t exactly new, but there seems to be a lot of activity in this space lately (look up the “Local First /lo-fi” movement).

The basic premise of a sync engine involves:

- You declaratively define what data is seem by what client (authorization)

- The sync engine then mirrors over this data to the client, usually using websockets and in near real-time

- Many sync engines have their own, often proprietary backend storage layer, but at least a few of them also support connecting to your own data source. Being able to connect to your own data source was key for me.

I researched this space pretty extensively in early 2025 (so things may have changed since then). I even tried a few of the top contenders:

- InstantDB

- Triplit

- Powersync

InstantDB was definitely the simplest to use. Using it is as simple as calling the useState react hook (actually a useQuery hook provided by their client library). The main blockers for me however were:

- It doesn’t allow me to connect it to my own postgres database. Instant is powered on the backend by a managed mulit-tenant postgres hosted by Instant. This also made me question reliability: could another app’s expensive queries affect my own app’s performance?

- It didn’t support a normalized datastore. Instant caches at a query level, so things ‘mostly’ appear to work offline. However, this cache isn’t normalized, so you can have different cached queries that return different values for the same underlying entity.

Triplit felt almost as simple. Triplit is built on the concept of “triples” (data structures representing 3 things: a subject, a predicate, and an object). It even allows connecting to your own database.

However, I found that the query performance wasn’t very good, especially when I had lists of components that each had their own userQuery hooks to fetch data.

Powersync is what I ended up settling on